The Gilboa Walk, a remnant of Israeli togetherness

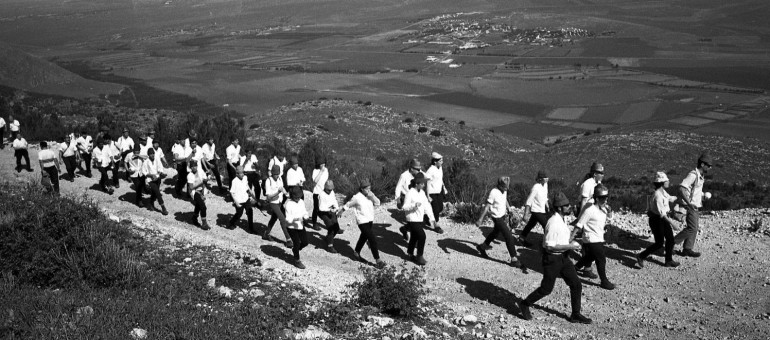

The 50th Gilboa Walk planned for this weekend is the last of the large popular walks still held in Israel and the only one that attracts participants from abroad. The mass walks have declined in past decades, perhaps as a reflection of the changes in Israeli society.

“Once we used to walk 30 or 40 kilometers and nobody thought it was a big deal,” says Izidor Sebag, 78. “The walks lasted four consecutive days with sleeping out of doors, on the trail, and we didn’t stop singing.”

“The Gilboa Walk was our training for the more difficult hike to Jerusalem. Those were different times, when walks in Israel were much more popular. They even published a special newspaper for the event. Army Radio and Israel Radio covered it live for four days,” he says.

Sebag, who has turned the treks into his life project, has taken part in every Gilboa walk that was held. This year he’ll take part in it for the 50th consecutive year, in addition to several other walks he plans to participate in. Asked why, he promptly replies “for the view. There’s nothing more beautiful than walking in the Gilboa landscape. Then there’s the company. I walk in a group and it’s a fantastic feeling. In recent years I’ve been organizing pensioners’ groups from a fertilizer plant I worked in for 40 years. And there’s also the sports matter. But age leaves its mark. I have no problem walking 10 kilometers but it’s not the same as when I was 20.”

This weekend’s walk could be seen as a remembrance of the way we were, when we were more like The Netherlands, where mass walks are hugely popular. It demonstrates the change in Israel, which once held several major walks. The largest one was the four-day hike to Jerusalem, in which tens of thousands took part every year. The Gilboa Walk is one of very few events that just cannot be criticized. It always takes place in the spring, when the violet Gilboa Iris, one of the most beautiful flowers in Israel, is in bloom. The mountain slopes are green and if it doesn’t rain – as it did last year – the hikers gaze on the magnificent view of Jezre’el Valley with Ein Harod and Kfar Yehezkel, the fields and plantations, water ponds and forests.

Shuka Aloni, 84, of Tel Yosef says he grew up at the foot of the Gilboa. Today he walks with his great grandchildren on one of the family trails. “The Gilboa Walk is an important project for the valley residents and we’re preserving it,” he says. “We feel nostalgia for the mountain. Until the Six Day War we didn’t go up to the top of it. Since ‘67 it has once again been part of the valley residents’ view.”

Aloni says the Gilboa Walk is unique because unlike most other walks, it takes place on the mountain, affording especially beautiful sights of the area. “From the top you see Palestine on one side and the Zionist project in the valley, with the kibbutzim and Kfar Yekezkel. The march gives us a picture of what we’ve done here so far,” he says.

Rafi Mann, historian and media scholar, sees the walks as a mirror of Israeli society and media and explains the change in their status. “In the ‘60s the four-day hike to Jerusalem was a national event. Its key aspect was the shared experience and sense of togetherness. A huge human swarm walked for a few days in the Jerusalem mountains. On Army Radio, for example, it was one of the major annual events and the IDF’s Training Command’s biggest annual project.

“In its heyday tens of thousands of people took part in this hike and the population was much smaller,” Mann continues. “The soldiers represented various units and the civilians came in groups from work places, government offices, industrial plants. It was a national event you had to be part of, an event comparable only to the Independence Day march. It was a huge logistical operation with large encampments and huge kitchens. Marching to Jerusalem was seen as a modern pilgrimage,” he says.

The walk’s popularity waned in the ‘70s, especially after the Yom Kippur War, which changed something fundamental in the collective Israeli mood, says Mann. “The Israeli experience since then has become much more individual. A walk is a collective event. The hikers want first and foremost a shared social experience and this is a lot less appealing in Israel of today,” he says. Mann compares the past walks to walking along the Israel Trail today. The latter is an individual activity or one for small groups. The walks’ success, in contrast, is measured by the number of participants.

The hikes have become local, communal events. Those who come to the Gilboa Walk want to express their identification with the region collectively. Part of the walks’ fall from grace, he says, also stems from the IDF’s drastic slash of its investment in mass events like this. It is no longer a national experience one must take part in.

Some 12,000 people take part in the Gilboa Walk. It is the only one recognized as an international event, with people from walking clubs abroad arriving especially to take part in it. About a third of the participants walk on Friday and the rest on Saturday. This year’s walk consists of three tracks – a 6-kilometer family track, a 13-kilometer popular track and an international two-day track of 20 kilometers each day. All the tracks converge at Ma’ayan Harod at the foot of the Gilboa mountains.

Mohse Gilad, Haaretz, 7 de abril de 2016